On a steamy November night in 2023, the Estadio Metropolitano in Barranquilla was packed for a crucial World Cup qualifier between Colombia and Brazil. In the 79th minute, the match was tied 1-1 when a cross came in from the right. Colombia and Liverpool FC forward Luis Díaz leaped ahead of his defender and thumped a powerful header into the opposite side of the net for his second goal of the evening. The sea of yellow jerseys in the stadium exploded into loud screams of jubilation and ecstasy as the announcer tore into the quintessential Spanish call “Gooooooooooooooollllllll.” As the camera panned to celebrations among the players, coaches, and fans, the focus turned to one particularly emotional supporter in the stands, Luis Manuel Díaz, father of the goalscorer. Díaz Sr. was punching his arms into the air, had tears in his eyes, and he seemed to be held up by the woman behind him as if the moment had taken away his ability to stand. Witnessing one’s son score two goals to claim a surprise victory over five-time world champions Brazil would be enough to make any father’s heart swell with pride. However Díaz Sr. had perhaps an even greater reason to react emotionally.

Two weeks earlier, Díaz Sr. was being marched through the mountainous terrain of Colombia’s northern La Guajira province by armed rebels. He was wet, covered in insects, and sleep-deprived by the stress of the ordeal. In late October, he and his wife had been abducted at gunpoint from their home by gang members associated with the Marxist-Leninist guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (ELN). While his wife was released within hours, Díaz Sr. was dragged into the mountainous jungle near the Venezuelan border. Following 12 days of captivity and international outrage, he was finally released by his kidnappers on November 9, one week before Colombia’s match.

With soccer serving as such a key component of Colombia’s social fabric, it is unsurprising that the sport often finds itself hijacked by Colombia’s volatile political and criminal environment. This link was most infamously put on display during the “narco-football” era of the 1990s, a period that witnessed the Colombian national team inextricably linked to Pablo Escobar and cartel culture, and led to the murder of one of the nation’s most promising stars. However, recent government administrations, non-profit organizations, and professional teams have utilized soccer as a tool for peacebuilding as Colombia seeks to recover from over half a century of conflict and turmoil. This week, Explaining Offsides will explore how Colombian soccer has reflected the national struggle with civil conflict in the past and how soccer is being employed to sew together national social cohesion, aid the post-conflict reconciliation process, and navigate its current political challenges and threats to peace.

Conflict and “Narco-Football”

Even by Latin American standards, Colombia has endured one of the most violent and turbulent periods among nations in the Americas since the end of World War II. According to the National Center for Historical Memory, between 1964 and 2012, civil conflict and violence have culminated in over 220,000 dead. More than 60,000 cases of forced disappearance, sex-based crimes, and gender-based violence have occurred along with the recruitment of almost 6,500 child soldiers, and the displacement of almost 6 million Colombians. These morbid statistics do not include the over 200,000 killed between 1948 and 1958 during a horrific civil war known simply as La Violencia. In the 1960s, far-left paramilitary groups, including most notably the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the ELN, would form in the wake of the civil war and begin violent clashes with the Colombian government. These groups, and eventually far-right paramilitary groups such as the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), would terrorize Colombian citizens through decades of atrocities, kidnappings, and human rights abuses.

In the background of this conflict, the illicit cocaine trade would take hold of Colombia in the 1970s and 1980s. Paramilitary groups would turn to drug smuggling and extortion as their primary means of financing their operations. However, other criminal enterprises would arise to capitalize on the drug trade. This led to the appearance of new cartels that would profit off the cocaine industry, including the Medellín cartel headed by the notorious kingpin Pablo Escobar. Escobar’s legacy in Colombia is extremely complicated. On one hand, he is seen as a violent drug lord who brought about an unprecedented level of violence and terrorism to Medellín and Colombia, which led to thousands of deaths. However, he is seen by some as a Robin Hood-esque character who used some of his vast ill-gotten wealth to fund housing and community projects in the city which benefited thousands of Medellín’s most impoverished citizens.

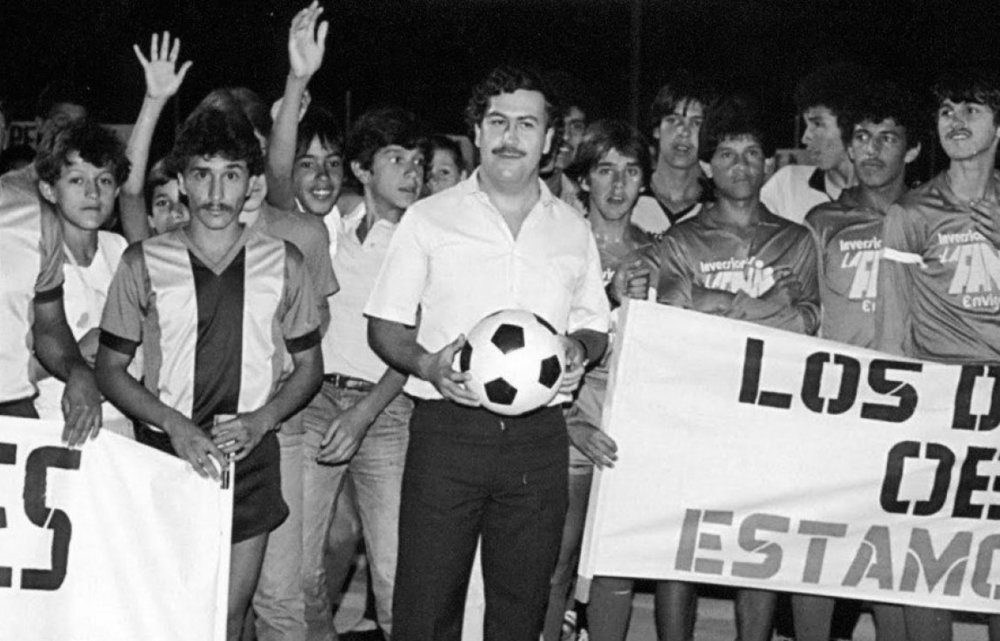

Notably, Pablo Escobar was a die-hard soccer fan, and his influence on the sport coincided with the Colombian national team’s golden generation of the late 1980s and early 1990s. He funded the construction of soccer fields, paid star players to participate in exhibition matches at his estate, and invested heavily in Medellín’s local team Atlético Nacional which would go on to be crowned South American champions following their triumph in the 1989 Copa Libertadores. However, he also ordered the assassination of a referee that ruled against Atlético Nacional in a game and contributed to the increased influence of organized crime in Colombian soccer. Escobar’s associate Gonzalo Gacha became the owner of Bogota’s Millonarios FC, and the rival Cali cartel was allegedly connected to América de Cali S.A. This era would come to be nicknamed “narco-football.”

Following the 1990 FIFA World Cup in which Colombia advanced past the first round, they entered the 1994 edition in incredible form featuring stars such as Carlos Valderrama, Faustino Asprilla, and Freddy Rincón. Colombia had dominated the continental qualification stage, dismantling then-South American champions Argentina 5-0. Pelé himself made the bold prediction that Colombia would win the World Cup. The team offered a contrasting image to the ongoing cartel conflicts that had been dominating the international narrative about the nation, and with Pablo Escobar’s death in 1993, many saw the tournament as an opportunity to demonstrate a Colombia that was emerging from violent conflict. As Dr. Peter Watson, an expert on Colombian soccer and politics, described it:

“Soccer was associated with a tropicalized image of the country through accompanying music on television broadcasts as well as advertising, which created a more positive identity of happiness, celebration, and flair linked to the Colombian Caribbean.” – Dr. Peter Watson

However, despite their great form in the lead-up to the tournament, Colombia’s campaign at the 1994 FIFA World Cup was an unmitigated disaster. Prior to the tournament, the eccentric goalkeeper René Higuita, who starred at the 1990 tournament and had alleged ties to Pablo Escobar, was imprisoned for seven months for serving as a mediator in a cartel-related kidnapping. Following Colombia’s loss to Romania in their opening game, death threats were called in against forward Gabriel Gomez and head coach Francisco Maturana. Unknown callers allegedly representing more powerful figures threatened the life of both the coach and the player if Gomez played in their next game against the United States. Gomez did not play in that crucial game, and he flew back to Colombia immediately after the match as death threats were allegedly also directed against his family. Colombia lost 2-1 to the United States, ensuring their elimination from the tournament. The winning goal came when American defender John Harkes crossed a ball that Colombian defender Andrés Escobar (no relation to Pablo) attempted to clear but accidentally directed into his own goal.

Andrés Escobar, nicknamed “El Caballero de Futbol” (The Gentleman of Soccer), was a rising star both for Colombia and Atlético Nacional. Ten days after his own goal, Escobar was confronted by a group of men outside of a nightclub in Medellín. Following heckling from the group, one of the men drew a .38 caliber pistol and shot Escobar six times. Escobar was murdered at just 27 years of age. Many reports allege that after each shot, the gunman yelled “Goal!” to mock him. It would later emerge that the assailant was a bodyguard for the Gallón brothers. Drug traffickers within the Medellín cartel had allegedly bet and lost large sums of money on the national team at the FIFA World Cup, and the slaying was retaliation. Escobar’s assassination was the darkest moment in the history of Colombian soccer, and likely the FIFA World Cup as a whole. The tournament that was supposed to symbolize Colombia’s recovery only further emphasized the nation’s slide into senseless violence.

In the years that followed, the national team continued to mirror the ongoing strife in Colombia. Despite qualifying for the 1998 FIFA World Cup, forward Ántony de Ávila would cause controversy by allegedly dedicating his qualification-sealing goal to imprisoned members of the Cali cartel. He would later be arrested in 2021 in Italy for his alleged involvement in international drug trafficking. Despite hosting and winning the 2001 Copa América, the nation’s only South American title, Colombia would again be marred by negative headlines as FARC increased its activities in the lead-up to the tournament. A series of bombings killed 12 people, and the vice president of the Colombian Football Federation was kidnapped (though released soon after). Due to security concerns, the tournament had originally been cancelled 10 days before the opening match, only to be reinstated a few days later. This created organizational chaos as Argentina withdrew from the tournament citing safety concerns, and Canada pulled out due to logistical problems having already disbanded the team camp after the original cancellation, leading to last-minute invitations to Costa Rica and Honduras. Though there were no reported incidents at the tournament, the violence in the lead-up and the disorderly cancellation and reinstatement of the tournament further shed a poor light on Colombia’s violent domestic conflict.

Colombia’s “National Unity Project”

Soccer’s reputation as a mirror of Colombia’s domestic struggles began to change in 2010 when Juan Manuel Santos took office as President of Colombia. President Santos made peacebuilding a key focus of his eight years in office. In 2012, Santos opened peace negotiations with FARC leadership with the goal of bringing an end to the decades-long conflict with far-left rebel groups. Following four years of mediation, opposition from conservative politicians including former President Álvaro Uribe, and an initially rejected agreement, the Colombian government and FARC leaders signed a historic peace accord in November 2016 that brought an official end to over half a century of warfare.

One of the defining features of the negotiations was the use of sport as a catalyst for Santos’ “national unity project.” President Santos was a very vocal supporter of the national team (sometimes referred to by its nickname Los Cafeteros, “The Coffeemakers”) and an explicit proponent of the power of sport to engender national social cohesion. His government frequently emphasized the power of sport and peacebuilding, with the Ministry of Interior releasing a report that claimed that soccer was “the sport that integrates and transforms us. There is no other sport that identifies us more as a nation; it unites us, ignoring political, racial, sexual preference or religious distinctions.”

Social media became a crucial tool of the Santos government not only to root on the success of the national team, but also to emphasize the importance of soccer as a unifying force during the post-conflict healing process. In 1,048 tweets from the President’s official and personal Twitter accounts, Santos mentioned the national team 514 times, referenced “all Colombians” 174 times, and mentioned the term “unity” 136 times. The President referred to national team head coach José Pekerman and his team as the “maximum symbol of national unity,” and he frequently emphasized the importance of the team’s unifying spirit with the hashtag, #UnidosPorUnPaís (United For A Country), a saying that was sewn onto the collars of the national team jersey.

It wasn’t only the national government that openly expressed its support for the national team. Throughout the negotiations, representatives from FARC also made their allegiance to the national team well known. FARC leaders and negotiators would frequently show up to talks and meetings with the government dressed in the national team jersey, and they openly celebrated national team victories on social media during qualification. Prior to Colombia’s opening match at the 2014 FIFA World Cup, FARC released an open letter of support addressed to the team which stated:

“In the name of every FARC guerrilla, today in talks to achieve peace with social justice for all, we raise our hopes for new triumphs that will bring happiness to every fellow patriot. We will be with the national team in the good times and the bad, supporting them to the very end […] We have the dream that soccer, as part of the path towards respect and tolerance, can, at this time, grant us some moments of joy or entertainment that can ease minds, and moderate feelings, and help us find the best path towards reconciliation” – FARC open letter to Colombian national team prior to their 2014 FIFA World Cup campaign

It is never reasonable to pin the hopes of negotiations that seek to end decades of violence on the success of a sports team. However, it certainly did not hurt that the peace process took place during the national team’s most successful period. In 2011, Colombia hosted the FIFA U-20 World Cup, soccer’s premier youth world championship. In contrast to the controversies that sullied their previous attempt at hosting a major international tournament ten years earlier, this youth World Cup was a tremendous success for Colombia. The tournament took place without any major disturbances, inspired global sponsorship and investment in Colombian sports infrastructure, and led to a boost in Colombian youth participation in soccer. Furthermore, the Colombian team advanced to the quarterfinals of the tournament by playing an exciting attacking style of soccer that drew widespread praise domestically and internationally. This team featured new young talents like James Rodríguez and Luis Muriel who would develop into global superstars in the years ahead.

Los Cafeteros then qualified for the 2014 FIFA World Cup, their first in 16 years, in dominant fashion, finishing second in South American qualification behind Lionel Messi-led Argentina. At the FIFA 2014 World Cup, Colombia was outstanding. The team finished first in their group with emphatic victories over Greece, Côte d’Ivoire, and Japan. They defeated Uruguay in the Round of 16, and were unlucky to be eliminated by Brazil in the quarterfinals after a hard-fought, competitive match. Colombia once again played attractive attacking soccer, scoring 12 goals in five games. James Rodríguez was catapulted to superstardom by scoring the most goals at the tournament (6), and his audacious long-range volley against Uruguay was awarded the FIFA Puskas Award for best goal in world soccer in 2014. The team played most of their games in front of overwhelming Colombian support as fans turned the stadiums into seas of yellow jerseys. Upon elimination, the team was greeted by tens of thousands of proud fans in the streets of Bogotá. To date, this remains Colombia’s best ever performance at the World Cup. The national team would continue their good form by finishing third at the 2016 Copa América and once again advancing out of the group stage in first place at the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia.

A Tool for Rehabilitation and Development

One of the key components of the multi-faceted peace agreement is the demobilization, disarmament, and rehabilitation of former FARC guerrilla fighters. For peace and transitional justice to succeed in Colombia, it is crucial that former combatants are not only removed from conflict but also empowered to succeed in a new Colombian society. Therefore, many peace stakeholders in the country have again employed soccer as a tool for rehabilitation, reconciliation and development.

Following the signing of the peace accord, 7,000 former FARC combatants were relocated to 26 rehabilitation camps known as Territorial Spaces for Training and Reincorporation (ETCRs). Many of the ETCRs used soccer as a tool for reintegration. Representatives of the Colombian national sports body Coldeportes and the Commons Party, the legitimate political successor to FARC, regularly collaborated to organize matches and tournaments in the ETCRs that brought together former combatants with local and indigenous communities. These events aimed to improve relations between former guerrilla fighters and community members. Even prior to 2016, soccer was employed to foster cooperation and goodwill during the peace process. In 2013, Carlos Valderrama, one of the stars of the Colombian national team in the 1980s and 1990s, worked with both factions to organize peace matches for government and FARC negotiators in Cuba where the talks were taking place.

Beyond the framework of the peace process, there has also been increased focus on the importance of using soccer as a development tool for young people to grow important social and professional skills. There is also the implementation of soccer programs that target often marginalized communities, which face issues of crime and poverty with the goal to foster stronger community cohesion and civic duty to combat these challenges. In 2024, a group of academics who specialized in sport science, medicine, physical education, and psychology performed a study that examined projects led by the Colombianitos Foundation, a non-profit that aims to use soccer as a social development tool for Colombian youth. They found that these programs had made positive impacts in a variety of distinct ways.

First, these sports programs contribute significantly to the personal growth of young participants, particularly as they relate to the development of positive social behaviors; non-violent conflict resolution skills; and sensitivity to different ethnic groups, genders, and social backgrounds. Second, these projects help break down social stigmas by creating opportunities for different communities and participants to interact constructively with each other, breaking down existing negative stereotypes and prejudices. Finally, these initiatives support community growth by improving communal social cohesion by providing events and activities where community members can gather and interact, and by engendering a sense of civic responsibility towards one’s community, thus fostering a positive identity that is attached to one’s local social structure.

Déjà Vu

Much like they did at the last American-hosted World Cup in 1994, the Colombian team enters this summer’s tournament as their nation finds itself at a crucial socio-political crossroads. Despite the official end of the conflict in 2016, the implementation of the promises made in the peace agreements has been slower than hoped. Furthermore, though the disarmament of FARC was a turning point, there remain other paramilitary groups, most notably the ELN, as well as approximately 5,000 FARC dissidents who have rejected the peace deal and are continuing to cause havoc in vulnerable regions, albeit at a reduced capacity. These remaining fighters have more deeply immersed themselves in drug trafficking and have expanded their illicit operations across Colombia’s porous border with their troublesome neighbor, Venezuela.

This contentious situation has drawn the notable ire and focus of the Trump administration in recent months. In September and October 2025, the U.S. Navy conducted a series of targeted strikes on numerous vessels in the Caribbean Sea off the coast of Colombia and Venezuela which the President and the U.S. Department of Defense alleged to be preventive defensive operations against “narco-terrorists.” It later emerged that among the over 80 people killed in these attacks was a Colombian fisherman, an action that human rights groups have referred to as an extrajudicial killing. When Colombian President Gustavo Petro referred to the military strikes as “murder,” President Trump fired back viciously on social media, calling President Petro “an illegal drug dealer.”

Tensions between the United States and Colombia climaxed when, following the U.S. Armed Forces January 2026 bombing of Caracas and capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, President Trump appeared to threaten President Petro with a similar fate stating that the elected Colombian leader “better wise up or he’ll be next.” In response, President Petro called Trump’s attack on Venezuela an “assault on the sovereignty” of Latin America, and the Colombian Ministry of Defense announced increased security around the President. In a bizarre moment of solidarity, the ELN released a statement condemning the capture of President Maduro, referring to the incident as an “imperialist aggression against the continent.” At the time of this article’s publication, tensions remain high. Though President Petro has agreed to an official visit to the White House in February where the world leaders will apparently discuss their relationship and strategies for reducing the flow of illegal narcotics from Colombia into the United States via more diplomatic avenues.

In another parallel to 1994, the Colombian national team will arrive in the United States in excellent form. Following a dip in results and a failure to qualify for the 2022 World Cup, the Colombian team returned to its winning ways going on an unprecedented 28-game, 29-month unbeaten run, during which Los Cafeteros vanquished powerhouses Germany, Brazil, and Spain. During this streak, Colombia also demolished the United States national team 5-1, a beatdown that the author of this article witnessed in-person at FedEx Field in Landover, Maryland. Colombia would finish runners-up at the 2024 Copa América where only a late overtime goal from Argentina’s Lautaro Martínez prevented Los Cafeteros from winning their second South American championship. Following another dominant qualification campaign, Colombia entered the 2026 World Cup expecting to go far with a new crop of stars, as well as the aging yet prolific James Rodríguez, who, despite being in the latter stages of his career, has found new life playing with the national team.

Stoppage Time

Colombia’s history can be characterized by the term “resilience.” It takes unfathomable resilience for a population to endure over half a century of violence and insecurity to begin the implementation of a roadmap to peace. It takes an inspiring amount of perseverance for a team to survive the infiltration of drug traffickers, the kidnapping of family members, and the murder of a star player, only to emerge as a unifying thread in the nation’s delicate social fabric. Despite a past filled with bloodshed and fear, Colombia’s ability to find creative ways to achieve progress speaks to the unshakeable character of Colombian citizens. The recent gut-wrenching yet heartwarming story of Luis Manuel Díaz’s survival provides yet another case study in Colombian defiance, perseverance, and courage. Colombians around the world will be praying for another magical World Cup performance that can once again captivate and unify a nation. However, most will also agree that just as important as the performance on the field is the desire to leave the tournament in the USA having presented a Colombia that is more peaceful, joyful, and hopeful than the violent, tragic, and deeply-wounded image that Colombia left at the previous United States World Cup in 1994.

Leave a comment