Kickoff

On an overcast November Saturday along Spain’s eastern Mediterranean coast, global superstars Kylian Mbappé, Jude Bellingham, and Vinícius Jr. were supposed to step onto the pitch at the Estadio de Mestalla in Valencia for Real Madrid’s matchup against Valencia CF. Yet on a day when tens of thousands of local fans would have piled into the stands to cheer on their team, stadiums across the autonomous Valencian Community sat empty. Three days earlier, on October 29, 2024, the provinces of Valencia, Castellón, and Albacete were ravaged by a storm that dumped nearly a year’s worth of rain on Valencia in just eight hours. Floodwaters as deep as ten feet turned local streets and highways into rivers and rapids, sweeping away cars, homes, and bridges. The 2024 Valencia floods killed more than 237 people and devastated Eastern Spain. In light of the tragedy, the Spanish Football Federation made the obvious decision to postpone all professional matches in the region, as Valencians turned their attention to rescue efforts.

This tragedy seems to be yet another disastrous consequence of climate change and the failure of national and international governments to take the necessary steps to combat environmental degradation. It is rare, however, for members of soccer’s global community to turn their attention to the sport’s role in both exacerbating climate change and harnessing its potential to influence environmental action. This week, Explaining Offsides will examine global soccer’s ties to climate change and climate action. Focusing on Spain—co-host of the 2030 FIFA World Cup—this article highlights how climate change has negatively impacted the development of soccer in the Mediterranean region and how the global soccer community can set positive examples for local communities, governing bodies, and stakeholders engaging in climate action.

When it Rains, It Pours

The Spanish Floods of 2024 were the deadliest natural disaster witnessed in Europe in decades. However, the floods that ravaged Valencia were far from the only deadly deluge that struck Europe that year. Earlier that same month, 27 people were killed by flooding in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In June, six people were killed by flooding in Southern Germany, and over the span of a week in September 2024, a series of floods killed 27 people spread throughout five countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Prof. Conor Murphy, at the National University of Ireland Maynooth Climate Research Centre, attributes the rise in extreme flooding events in Europe to three primary causes among others related to climate change.

First, sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and Mediterranean are increasing at a frightening rate. The median sea surface temperature of the Mediterranean waters reached an extremely abnormal 86°F (30°C) at certain points off the coast of Spain, France, and Italy while the sea average hovers around 78.8°F (26°C). Over 90% of additional heat emitted through greenhouse gases is absorbed by large bodies of water, namely oceans and seas. Elevated water temperatures contribute to the moisture and heat energy that destabilizes atmospheric conditions and increases the likelihood of extreme weather events. As we have seen in Spain, the Mediterranean is increasingly on the receiving end of such deadly weather phenomena.

Second, the rise in temperatures allows for more moisture to be contained within the atmosphere, leading to more intense rainfall during precipitation events. Indeed, Spain is getting hotter. Summer 2025 was Spain’s hottest summer on record. The country’s national weather agency (AEMET) reported an average temperature of 75.5°F (24.2°C) from June 1st to August 31st, breaking the previous record from 2022. This was also 3.7°F (2.1°C) higher than the national average between 1991 and 2000. The highest temperature of this past summer in Spain was a staggering 119.3°F (45.8°C) recorded in Jerez de la Frontera on August 17.

Third, the warming of the Arctic is significantly disturbing traditional weather patterns in Europe, creating conditions that allow for extreme rainfall events. Though the effects of polar warming aren’t fully understood, many scientists believe that warming temperatures in the Arctic are destabilizing the polar jet stream. The polar jet stream is a large wind current that flows from North America over the North Atlantic and into Europe. When the jet stream is altered, the disruption allows for low-pressure systems to stall and dump higher levels of rainfall on one area. In Spain a low-pressure system trapped itself over the Iberian Peninsula, maintaining the worst rainfall over Valencia.

In contrast to these extreme flooding events, Spain is getting drier and even losing swaths of land to desert-like conditions in some areas. In 2023, Spain achieved an average annual precipitation of 21.1 inches (536 mm), a figure that places it below continental averages that usually hover somewhere between 30 and 36 inches per year. However, national annual rainfall data is somewhat skewed by Spain’s wet northern regions of Galicia, Asturia, and Cantabria, which regularly average between 60 and 80 inches of annual precipitation with some areas recording almost 160 inches (over 13 feet) of rainfall in some years. However, some provinces in the arid south can receive less than 12 inches of rainfall per year. There are even parts of Southern Spain that suffer from the effects of desertification in which fertile land degrades into desert-like conditions. This heat and lack of regular precipitation have also fueled the most destructive wildfire season in Spain’s history with roughly one million acres, an area roughly the size of Rhode Island, being reduced to ashes in 2025.

As Spain gets drier, water scarcity becomes a more immediate and threatening issue. According to the United Nations Environment Programme, the Mediterranean region is heating up at a 20% faster rate than the world average, and droughts in 2023 and 2024 saw nine million Spanish citizens, one-fifth of the population, face water usage restrictions. In 2025, water demand in Madrid exceeded 3.4 times the available water supply in the nation’s capital, and current projections suggest that by 2050 Madrid’s demand for water will exceed its supply by 4.5 times. In a tragic irony, a country that is facing water scarcity is experiencing deadly flooding as a result of rising temperatures, which contribute to an increasingly arid climate. Despite water scarcity threats, Madrid will likely host the World Cup Final in 2030.

Given the current impact of climate change on the lives of billions, it may seem insensitive, even insignificant to ponder the role of sport in climate change. However, in soccer, we are presented with an opportunity to frame the discourse on climate change, sustainability, and climate action into a discussion that is more digestible to a global audience than articles that list a range of alarming statistics.

Pitches in Peril

Though the connection between soccer and climate change is rarely discussed, the impact of negative weather on soccer is ever-present. In 2015, FIFA made the controversial decision to move the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar from June and July, when temperatures rise to an average high of 109.4°F (43°C), to November and December. Recently, the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup received many negative headlines as players and fans complained about having to play midday matches in 90°F+ heat, citing concerns for their safety. Marcos Llorente, midfielder for Atletico Madrid and the Spanish national team, stated the following after Madrid’s match against Paris Saint-Germain in Pasadena, California: “It’s impossible, terribly hot. My toenails were hurting; I couldn’t slow down or speed up. It was unbelievable.” Many now are expressing concern for the climate realities of playing the tournament against the backdrop of a hot American summer.

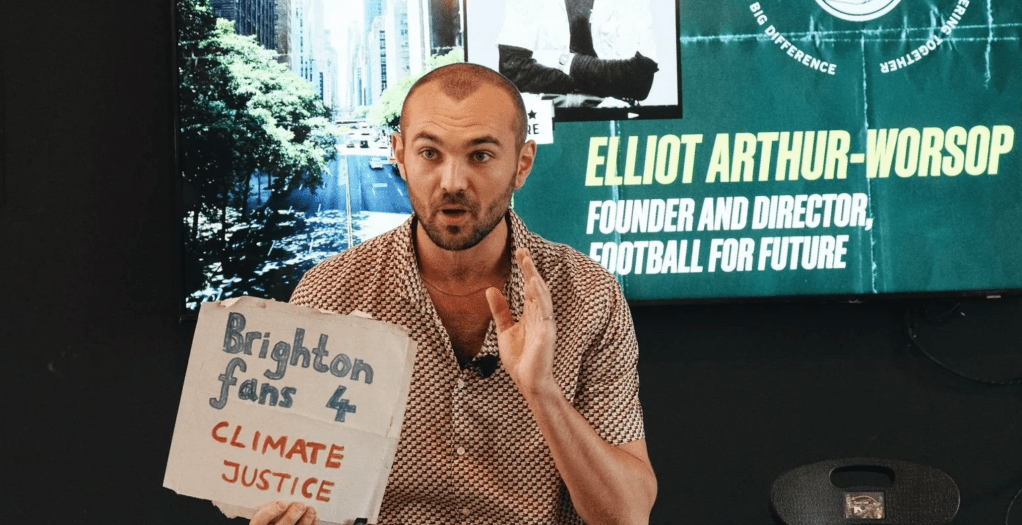

In 2025, Football Future and Common Ground released a groundbreaking report on the intersection of soccer, climate change, and sustainability entitled Pitches in Peril: How Climate Change Is Threatening Football. This marked the first time a global climate risk report that targeted soccer was drafted. The report presented the data in a unique way featuring vivid and engaging imagery and graphics, and focusing studies on host cities of the World Cup and home communities for some of the sport’s biggest stars like Kylian Mbappé and Lionel Messi.

The report delves into the effects of a variety of climate extremes from heat to wind to droughts, among other negative weather events. Starting with extreme heat, the report’s findings are deeply concerning. The study—which categorizes temperatures of over 95°F (35°C) as “unplayable”—found that by the end of 2025, 10 out of 16 host stadiums for the 2026 World Cup are projected to experience unplayable heat. It states that if current trends continue, Miami, Houston, Monterrey, and Dallas are projected to experience 100 to 160 days of unplayable heat conditions by 2050. Concerns about heat-related player safety at the upcoming World Cup have forced soccer’s top governing body to act. Last week, FIFA announced that at this summer’s tournament, each half will be paused after 22 minutes to allow for three-minute “hydration breaks.”

In the Mediterranean, there are concerns for Spain, Morocco, and Portugal’s suitability as hosts for the 2030 World Cup due to extreme heat conditions. The proposed host cities were announced in 2024, and several of them raise concerns. One of the potential host cities, Seville, is situated in the southern arid region of Andalucía (where the aforementioned Almería is also located) and has been referred to as “the frying pan of Europe” with temperatures soaring above 104°F (40°C) for three consecutive days in May 2025. Las Palmas, the capital of the Canary Islands, has also been proposed as a host city. Though summers in the Canaries are usually mild, Las Palmas is occasionally struck by a weather phenomenon known as a “calima.” Calimas occur when sand and dust from the Sahara Desert collect in the atmosphere and drift into Europe, especially the southern Iberian peninsula and the Canary Islands. Calimas can bring in heavy dust and haze which can cause respiratory issues and also produce temperatures that exceed 100°F. Morocco as a host is problematic from an extreme heat standpoint in cities like Marrakech where temperatures can soar above 100°F in peak summer months.

Another suggested host city is Valencia. As previously mentioned, there was a significant loss of human life, which cannot be quantified. However, there was also property devastation with over 48,000 homes destroyed and an economic fallout estimated in the tens of billions of dollars. Among the destruction were 150 regional soccer fields damaged with 15 completely destroyed. According to the Valencian Community Football Federation, 15% of players, coaches, and staff in the Valencian region were directly impacted by the floods. Lower league clubs such as CF Paiporta and Discobolo La Torre A.C have had their fields destroyed by the flooding. The town of Paiporta had been labeled the “ground zero” of the flooding, with over 62 residents dead, businesses and homes in ruins, and streets rendered impassable by debris and feet-high rivers of mud. These teams join a growing list of clubs, many of which are pillars of their local community, that have had their home grounds damaged or destroyed by flooding and heavy precipitation.

Crucially, the report points out that though major stadiums are sometimes impacted, community pitches and other facilities that are used primarily by grassroots organizations are disproportionately affected by climate change. Professional matches can be rescheduled and stadiums can be renovated. However, when local fields—particularly those located in underserved areas—are damaged or destroyed, local communities lose recreational and green spaces that are crucial not only to general morale, but also to young people who lose access to healthy and formative tools for personal and emotional development. Countless studies demonstrate how shared recreational green spaces improve community cohesion, encourage social development, reduce negative activities, and bolster the local environment. Losing these pitches to environmental disasters is more than stripping communities of soccer; it is denying them critical outlets for physical, emotional, environmental, and social well-being.

The devastating floods that took place in Valencia last year are the kind of extreme weather events that the Pitches in Peril report might refer to as “100-year events.” However, current environmental trends suggest that these disasters will occur more often without collective action from key decision-makers. Should excessive flooding or an extreme heatwave occur in Spain, Portugal, or Morocco while millions of soccer fans stream into the region for the 2030 FIFA World Cup, the potential physical and human damage could be catastrophic for the reputation of world soccer.

Soccer’s Role in Preventing Climate Catastrophes

The gloomy statistics above make it easy to fall into defeatism and question the extent to which soccer can have a positive impact on combating the negative effects of climate change. However, soccer finds itself in a unique position to influence change due to its global profile, especially at the World Cup. The Pitches in Peril report outlines numerous climate actions that soccer stakeholders at every level can take in order to more effectively combat the negative effects of climate change.

First, it calls upon major tournament organizers like FIFA and UEFA to enforce strict climate protection and sustainability standards at their major events. Prior to the 2024 European Championships in Germany, UEFA drafted a 40-page environmental, social, and governance (ESG) strategy which aimed to reduce the tournament’s negative climatic impact and implement sustainable event infrastructure projects. UEFA invested €30.6 million in ESG initiatives, and its ESG strategy allowed for the 2024 championships to leave a carbon footprint that was 174,000 tons less in CO₂-equivalent emissions than what was originally projected. UEFA also invested a further €7.9 million in its climate fund. This fund will be shared with 200 German clubs to help finance their own projects related to renewable energy, waste management, and energy efficiency. In the lead-up to the 2026 World Cup, FIFA released its Sustainability & Human Rights Strategy which provides a general outline for working with local stakeholders in the United States, Mexico, and Canada to develop sustainable infrastructure, mitigate the tournament’s climate impact, reduce waste, and promote biodiversity and conservation.

Despite this, many environmental scientists and activists are skeptical of FIFA’s commitment to climate sustainability. Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR) claim that this summer’s tournament will be “the most climate-damaging” World Cup in history due to its projected heavy carbon footprint with the tournament’s expansion from 32 to 48 teams and increased reliance on air travel among other factors. Another report from the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) has accused FIFA of failing to take adequate steps to meet its own climate goals. The report highlights the need for FIFA and other tournament organizers to not only take more active steps to implement stricter sustainability standards in their tournaments, but to pressure and/or cut ties with sponsors and hosts that fail to meet the same commitments.

Next, Pitches in Peril calls upon national sports governing bodies and individual clubs to create their own sustainability strategies and form their own working groups that will join with communities to create sustainability and environmental protection frameworks. In the UK, Premier League clubs like Brighton & Hove Albion, Brentford, and Tottenham have implemented a variety of sustainability and green initiatives such as water reuse projects, waste diversion systems, low-emissions transportation, and green space creation. In support of these green projects, England’s national soccer governing body, The Football Association (FA) launched a sustainable energy program called the Greener Game in 2024, a five-year program that will invest £1.5 million annually in sustainable energy improvements at FA clubs. Forest Green Rovers F.C. in the 5th tier of English soccer is the gold (or green) standard having gained international recognition for becoming the world’s first carbon neutral football club as it is powered entirely by green energy. The team has earned the nickname “the greenest club in the world” with its recycled water field irrigation system, solar panels, all-electric groundskeeping equipment, and all-vegan dining in their stadium.

Organizations like Football for Future work to empower professional players to use their platforms to promote climate action in ways that policymakers and climate scientists cannot. Soccer players who are passionate about sustainability can sometimes feel intimidated sharing their perspectives as they may feel under-qualified. However, they possess the unique ability to not only engage a large audience, but also to tie issues of climate change to communities and grassroots soccer. Serge Gnabry, forward for Bayern Munich and the German national team, has spoken publicly about how climate change and extreme weather have denied young people in many communities in Côte d’Ivoire (birthplace of his father) from having access to safe recreational spaces, thus negatively impacting youth development in the country. Another German international, Kai Havertz of Arsenal spoke about how he was inspired to learn more about climate change in 2021 following deadly floods in Germany that killed 180 people. Finally, Juan Mata, World Cup and European Championship winner with Spain, had the following response to the Valencia floods:

“As someone from Spain, I can’t ignore the reality of the climate crisis. We’re seeing it more clearly than ever, from record-breaking heatwaves to floods like the ones in Valencia. Football has always brought people together, but now it’s also a reminder of what we stand to lose if we don’t act. We all have a role to play in facing this challenge, for our communities today and for future generations.”

Finally, the Pitches in Peril report places a degree of responsibility on soccer fans. According to the study’s surveys, soccer fans overwhelmingly support sustainability and climate action initiatives in the sport. These surveys also show that fans are not only willing to support climate action from their local clubs, but that their clubs tackling climate change would actually strengthen their team loyalty and community attachment. In response, the report suggests that local clubs, grassroots organizations, and even fans themselves should take active steps to engage in climate action. Football for Future and Common Goal have put together a handbook that instructs fan communities and grassroots organizations on organizing climate-conscious initiatives. This guide provides recommendations on how to raise awareness of climate risks in their communities, how to organize climate action working groups, and how to engage with professional clubs and elite organizations to enact sustainability and adaptation standards.

As studies from Football For Future, SGR, EDF, and other organizations have shown, there are a variety of approaches that soccer stakeholders, from individual fans to clubs to soccer governing bodies, can take to make significant progress in making soccer more eco-friendly and to demonstrate how these initiatives can serve as a blueprint for policymakers at all levels in tackling climate change.

Stoppage Time

On November 23, 2025, 43,975 crowded into the Estadio Mestalla for a match between Valencia CF and Real Betis, the first game in Valencia since the flooding. In an emotional pregame ceremony, players walked out onto the field where they were greeted by a massive Senyera, the Valencian regional flag, at the center of field as the Valencian regional anthem, Himne de l’Exposició, was performed by musicians playing traditional local instruments such as the dolcaina and the tabalet drum. Players from both teams proceeded to place a large black ribbon on the center of the field in front of the flag. As the music continued, fans around the stadium held yellow and red squares of paper to form an even larger Senyera which wrapped around the entire stadium. The camera panned to the tear-soaked players, coaches, and fans. At that moment, a large black banner unfurls from the top of the stadium to the field. At the top in bold, it reads “AMUNT VALENCIANS” (“Onward Valencia!” in the local dialect) followed by a list of the towns most heavily devastated by the floods. As the moment of silence begins, the tens of thousands of fans in the stadium reflect on the over 230 members of the community lost in the disaster. Included among the dead was José Castillejo. Castillejo, a midfielder, played for a variety of lower league clubs in the region and featured in Valencia CF’s youth academy and under-19 team. He was only 28 years old. Valencia would go on to win the emotionally-charged game 4-2.

Spain is the consensus favorite to raise the World Cup trophy this summer. The same year of the tragic floods in Valencia also saw the Spanish national team win the European Championships, the Spanish Olympic team win the gold medal in Paris in men’s soccer, and Real Madrid win the UEFA Champions League. Even the women’s national team is reigning world champions, and a Spaniard has been crowned as the best woman footballer in the world the last five years. On the field, Spain is on top of the world. However, as current climate trends continue to degrade, Spain as a nation will be on the front lines of Europe’s battle with climate change for many years to come. Millions of Spaniards, especially youth, will lose access to soccer in the decades ahead if a concerted and multitiered effort to combat the effects of climate change is not implemented with the urgency required.

Over the years, the issue of climate change has frequently been referred to in the future tense. It has often appeared as a warning of what could happen, how high temperatures will increase, and how much sea level could rise. Climate change must now also be spoken about in the present tense. It is happening right now. Temperatures continue to rise. People are dying today from the consequences of environmental neglect. However, despite this grave outlook, it is crucial that members of the soccer community who wish to engage in climate action are not discouraged. Sport engages people around the world in ways that traditional institutions cannot replicate. Genuine efforts by fans, players, clubs, tournament organizers, and soccer governing bodies will go a long way toward positively influencing decision-makers as they navigate environmental challenges. The fact that the role of soccer in climate action is being discussed is a massive step in the right direction. Resilience and commitment by key soccer stakeholders will ensure that future generations are able to safely access this beloved sport and the green recreational spaces that it inhabits.

Leave a comment