Kickoff

Soccer fans in Brazil have fallen out of love with their national team, and there’s data to back this up. In a 2025 survey by O Globo, only 15.9% of participants described themselves as “fanatic” fans of the national team, 48.5% indicating that they cared little about the Brazil team. A Datafolha survey showed the number of fans who have a “great interest” in the national team has dropped from 51% in 2006 to 22% in 2022 while the number of Brazilians with “no interest” has climbed from only 10% in 2006 to 51% in 2022. So what happened? Brazil, with five World Cup triumphs, more than any other nation, is famously a soccer-obsessed country. Despite not having won the World Cup since 2002, the Seleção Canarinho (the “canary squad” after their iconic yellow jerseys) have been crowned continental champions three times since their last World Cup title, and stars like Neymar, Vinicius Jr., and Raphinha have been among the best footballers in the world in recent years. Yet, an apathy and weariness are felt by many Brazilians towards this team due to recent political and cultural turmoil. This week in Explaining Offsides, we will examine how the national team has represented a political shift from left-wing pro-democracy movements of the past to far-right extremism, and how the failures of the national team represent not only an ongoing identity crisis in Brazilian culture but also a deep ideological rift that divides Brazilian society.

Corinthians Democracy

Members of the Selecão once represented not only a uniquely Brazilian brand of success on the field, but a belief in participative democracy and a hope for a more prosperous, equitable and united future for South America’s largest country. São Paulo-based team Sport Club Corinthians Paulista, known simply as “Corinthians,” is historically one of the most popular and successful clubs in Brazil. Corinthians has a reputation as a left-wing club having been founded in 1910 by immigrant railway workers. In an era when soccer was a sport played primarily by white elites in Brazil, Corinthians proudly fielded players of African descent in the 1930s and 1940s, including Teleco and Baltazar. In the 1970s and 1980s, São Paulo was considered the epicenter of the resistance to the military junta that had been in power since the 1964 coup d’état with a series of student and workers strikes which would contribute to the rise of future leaders of Brazil such as current President, Lula da Silva—known simply as “Lula.”

This rebellious spirit was embodied by the captain of both Corinthians and the Brazil national team, Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira, or simply “Sócrates.” Sócrates earned a reputation as a maverick “anti-footballer” known for his intellectual interests, outspoken left-wing political views, and his medical degree, which earned him the nickname “Dr. Sócrates,”—ironic given his fondness for chain-smoking and heavy drinking. Years later while playing in Italy, he was asked about his favorite contemporary Italian soccer player. He stated, “I don’t know them. I’m here to read Gramsci in its original language and to study the history of the workers’ movement.” At the 1982 World Cup, Brazil and Sócrates captivated the world with their rhythmic, vibrant, and attacking style of play which embodied the spirit of Brazil’s vibrant culture. Despite their elimination at the hands of Italy, this squad is fondly remembered in Brazil as “the greatest team to never win the World Cup.”

Despite their storied profile, Corinthians struggled in 1981 having won only 4 games in the Brazilian Championship and finishing in 8th place at the regional state championships, a tournament in which they are usually dominant. The mercurial Sócrates frequently clashed with team management, which he viewed as an extension of Brazil’s authoritarian leadership. In response, club president Waldemir Pires appointed Adilson Monteiro Alves as technical director and tasked him with implementing a management system that would change the team’s fortunes. Alves felt that there were broken links between team management and the players which contributed to the discord that held the team back. He worked with Sócrates and other team leaders to implement an experimental decentralized system of management which empowered full participation by players and staff in club decisions.

This player-powered management ideology came to be known as “Corinthians Democracy” (Democracia Corinthiana). Corinthians Democracy was implemented through a new egalitarian operational structure which implemented a direct voting system for team and club decisions. This expanded far beyond simple tactics to include decisions on transfers, facility management, financial distribution of club revenue, as well as other routine club operations. The new hyper-democratic approach to management contributed to an improvement in team morale and increased a collective sense of ownership and involvement in the success of the team. This led to improved results on the field as Corinthians would go on to win the São Paulo state championships in 1982 and 1983 and in the boardroom, as the club paid off its debts and earned a net profit of $3 million. As Sócrates later described it:

“We chose by simple majority and everyone’s vote was absolutely equal to any other vote. A club director meant as much as a reserve goalkeeper. The administrator or masseur was as much a part of the team as me, the captain of the Brazilian national team. And this gave us an incredible shared sense of complicity, of the independence of everyone within a single team.”

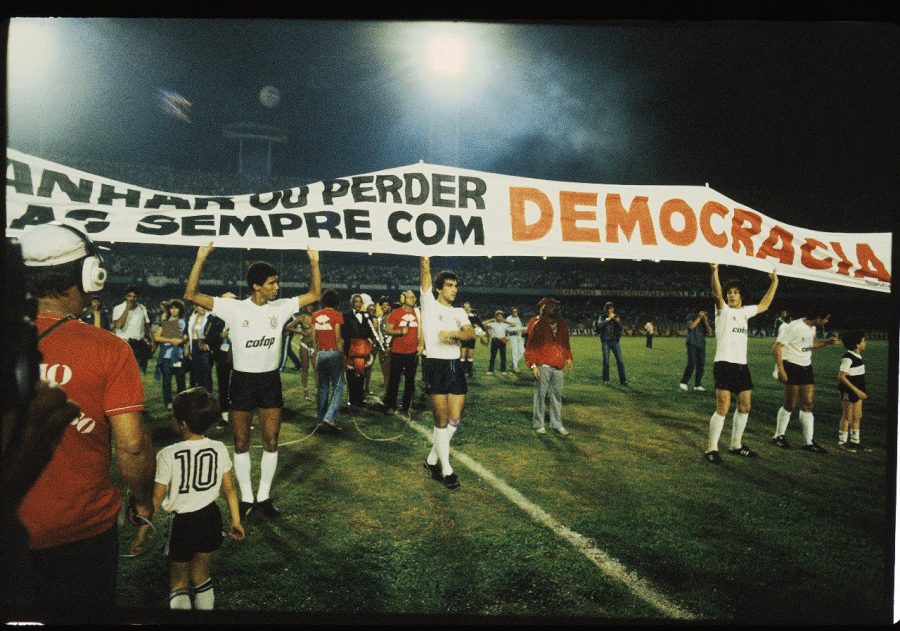

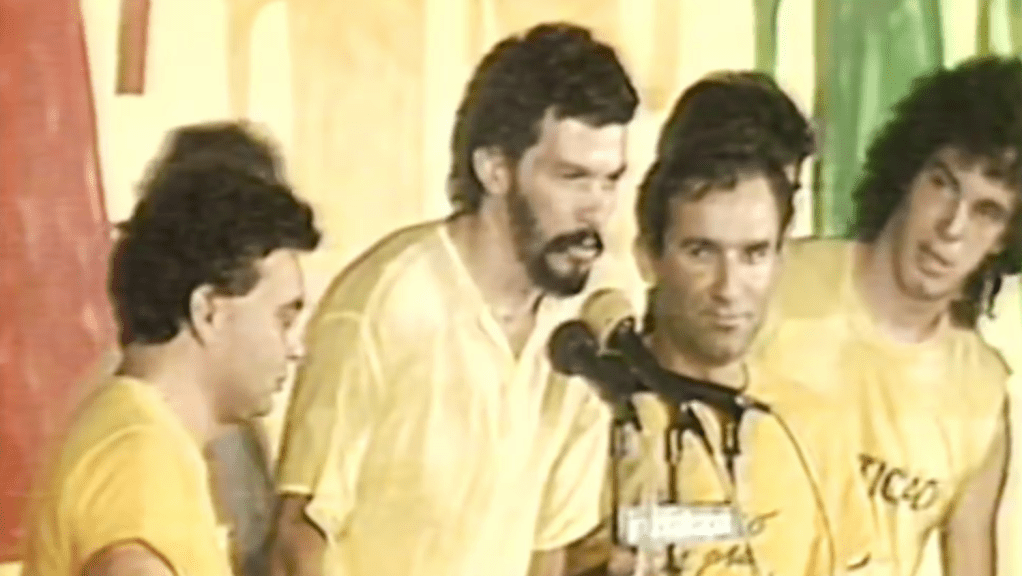

Emboldened by their on-field successes, the Corinthians’ players began to use their elevated platforms as athletes to advocate for similar democratic changes at the national level. They did this by printing political slogans on their shirts including “Direct [elections] now” (Diretas-já) and “I want to vote for the president” (Eu quero votar para presidente). When they won the 1982 state championship, they wore t-shirts with the word “Democracia” printed on the front, and upon winning the 1983 title, they unfurled a banner that stated “Win or lose, but always with democracy” (Ganhar ou perder mas sempre com democracia). In combination with the efforts of anti-junta activists, Corinthians team members joined the pro-democracy Diretas Já movement. Though the regime had slowly begun reintroducing democratic reforms, the movement called for direct presidential elections and the end of decades of military autocratic rule. Sócrates would speak out in the press stating, “I want to stay in my country to participate in the reconstruction. Whether it is working as a soccer player, sweeper, plumber, or doctor is another conversation.”

At an April 1984 rally in São Paulo, Sócrates, who had been receiving lucrative offers to play for clubs in Italy, delivered a speech to nearly 2 million protesters in which he promised to stay in Brazil if a parliamentary amendment that would allow for direct presidential elections was ratified. Despite enormous popular support, the amendment was rejected by the military government, and Sócrates moved to Italy to play for Fiorentina in Florence. However, the military leadership soon conceded to immense political and economic pressure within a year. The junta joined the opposition to elect Brazil’s first civilian president since 1964, Tancredo Neves, thus ending military rule. Sócrates would subsequently return to Brazil, joining Rio de Janeiro powerhouse Flamengo and rejoining three of his former Corinthians teammates on the Brazilian national team at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico.

The Death of Jogo Bonito

Sócrates and Corinthians had symbolized the resilience of the Brazilian people in the face of oppression, and the Brazilian national team continued to captivate the world with their samba-style soccer, appearing in three World Cup Finals in a row in the 1990s and 2000s, winning the 1994 and 2002 editions. Pelé had popularized the term jogo bonito in the 1970s, and this term came to characterize the fluidity and swagger of the Brazilian teams of the 1980s to the 2000s. Jogo bonito, as a soccer philosophy, is difficult to define, but it grew out of the impoverished favelas of Brazilian cities throughout the 20th century. Championed particularly by superstars from Zico and Sócrates in the 80s to Romário in the early 90s to Ronaldo and Ronaldinho in the late 90s and early 2000s, it was highlighted by close control and quick passing combinations developed from having to operate in small-sided games with improvised equipment in the most impoverished neighborhoods. In fact, many, if not most, of the greatest Brazilian players like Pelé, Ronaldo, Neymar, and Ronaldinho grew up and developed the fundamentals of their game in the compact streets of the favelas in major cities such as Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Belo Horizonte.

Most importantly, jogo bonito emphasizes rhythm and alegria (joy) as it stylistically combines the movements of capoeira with the rhythm of samba. The famed Nike ad campaign entitled “Joga Bonito” of the early-to-mid 2000s featured Ronaldo, Ronaldinho, and other Brazilian legends sharing dazzling freestyle tricks with the ball in a variety of shifting environments from the Seleção locker room to cramped alleyways to airport lounges. Brazilian music is featured prominently in the background, especially the famed 1960s bossa nova legend Sérgio Mendes—who experienced a resurgence in the mid-2000s partially due to this campaign—and the improvised style of Barbatuques, who emphasized “body percussion” to create their unique rhythmic style. This packaged Brazilian football into an approach to the sport with a sense of joy and freedom that gained them millions of admirers around the world. Brazilians developed a sense of national identity in soccer that celebrated artistry and freedom in contrast to the rigid and regimented nature of Europe and the West. It was not sufficient to win; one needed to win beautifully.

Yet the mid-2000s would mark a shift in Brazilian football that mirrored shifting global cultural patterns. At almost every World Cup since 2002, Brazil was eliminated in the quarterfinals by a European national team. The only exception came when they hosted in 2014, where Brazil advanced to the semifinals. However, this tournament was even more damaging to the Brazil national team, as the Seleção were traumatically battered 7–1 by eventual champions Germany in front of a horrified home crowd in Belo Horizonte. As Germany scored five goals in the first 25 minutes, images from the stadium portrayed Brazilian fans sobbing and screaming in agony in scenes almost resembling a population suffering the horrors of war. Some commentators have referred to this humiliating defeat as “The Day That Brazilian Football Died,” and indeed, this and other losses signified a shift in the way the world understood how soccer needed to be played.

Though sometimes ridiculed for a perceived lack of creativity, Europe’s more organized and methodical approach to modern tactics has become the new way of achieving success. Following Brazil’s 2002 triumph, every World Cup winner has come from Europe, with the sole exception of Argentina’s 2022 victory. Even then, Argentina is known among the Americas for its strong Italian and European roots, which have influenced its national identity in a way that distinguishes it notably from other South American countries. Beyond just the style of play, changes to labor laws governing athletes in Europe in the 1990s opened the door to previously unheard-of levels of investment, resources, and player influence, leading European leagues to be widely acknowledged as the best in the world.

Brazilian soccer prospects have taken notice. In previous generations, Brazil’s stars would spend their youth and early professional years at Brazilian clubs before moving to Europe in their early to mid-20s—or choosing to remain in Brazil. Nowadays, most of the best young Brazilian talents accept lucrative deals to move to Europe as teenagers to develop in the top leagues overseas. When Brazil last won the World Cup in 2002, 13 of the 23 players on the squad were playing for Brazilian clubs. At the most recent World Cup, however, only three of the 26 players were playing their club soccer in Brazil. This has created an issue for the Brazilian public, which struggles to develop strong bonds with players before they leave. Many Brazilians also feel that moving to Europe so early in a player’s development causes players to become “too European” in their approach to soccer. The result is a national team loaded with international superstars like Vinicius Jr., Endrick, and Estêvão—who all left Brazil at age 18—yet who find it difficult to connect with Brazilian fans and to merge their styles with teammates and coaches. These factors have contributed to a complicated internal team dynamic and comparatively poor results at the World Cup.

This shift in the style and makeup of the Brazilian national team has signaled the death of jogo bonito, and it has proven emblematic of the country’s ongoing struggles with a lack of national cohesion and a tenuous position on the international stage. As recent trends in world soccer have pulled Brazilian fans further away from their stars, recent Seleção squad members have also contributed to the nation’s deep political divide.

Bolsonaro, Neymar, and the Seleção’s embrace of the far-right

On the evening of October 30, 2022, supporters of Lula, the candidate for the left-leaning Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores), took to the streets across the country to celebrate his razor-thin presidential election victory over the far-right Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) incumbent Jair Bolsonaro. As the night wore on, videos emerged of the partygoers chanting, “Ey, Neymar, vai ter que declarar” (“Hey, Neymar, you will have to declare”). It seemed out of place—were they mocking Neymar, the Brazil national team’s star player? A month earlier, Neymar had posted a video on TikTok in which he pledged his support for Jair Bolsonaro, lip-syncing to the campaign jingle “Vota, vota e confirma, 22 é Bolsonaro” (“Vote, vote, and press ‘confirm,’ 22 is Bolsonaro”), referencing the then-President’s ballot number. Neymar had recently become entangled in several legal cases regarding alleged tax evasion, and some speculated that his support for Bolsonaro was an attempt to secure a presidential pardon—hence the “declare” taunt from Lula supporters.

But Neymar is not alone. Many former and current members of the national team, such as Thiago Silva, Lucas Moura, Dani Alves, Alisson, and Júlio César, had spoken out in support of Bolsonaro in the lead-up to the 2022 election. These declarations appeared to place the Seleção firmly in the far-right camp within an already deeply polarized Brazilian political environment. Left-leaning sportswriter and Sócrates confidant Juca Kfouri has argued that many Brazilian athletes who have become staunch “Bolsonaristas,” enriched by their professional success, are disconnected from the realities of modern Brazilian life and are primarily concerned with property and security issues—central themes of Bolsonaro’s campaign.

The last fifteen years have not been kind to Brazil. Like many countries, Brazil’s economy suffered in the wake of the 2007–2008 financial crisis and recession, and the nation’s pronounced economic inequality was further aggravated by numerous corruption scandals, most notably “Operation Car Wash,” which led to the impeachment and removal of President Dilma Rousseff. Even Brazil’s hosting of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics was tainted by corruption and controversy. The development of multi-billion-dollar projects in host cities deeply upset many working-class Brazilians, as poor neighborhoods were bulldozed to make way for sporting complexes and accommodations in the lead-up to the tournaments—many of which have since sat empty. As one fan put it after the humiliation of the 2014 World Cup defeat, “I hope this will make Brazilians realize that Brazil is no good at politics, education, health, and not even in soccer, which was all we had left.”

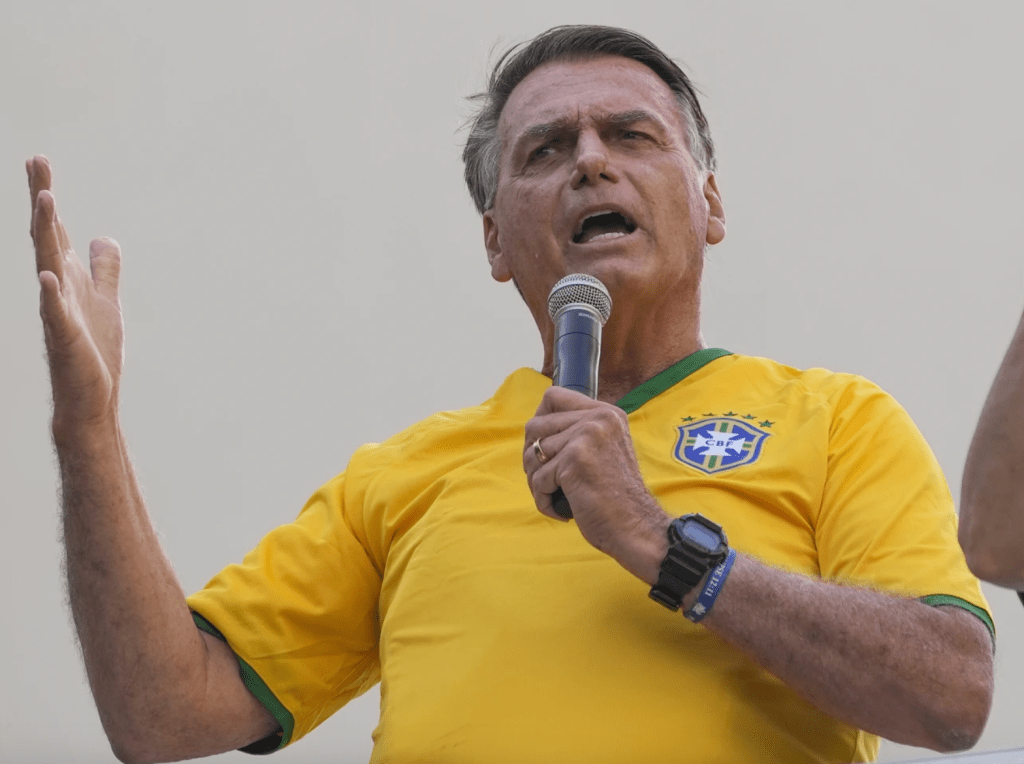

In this context, Jair Bolsonaro was able to garner significant popularity among Brazilians desperate for change. Much like Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, Bolsonaro relied heavily on populist rhetoric addressing corruption, crime, and poverty—messaging that preyed on citizens’ fears and insecurities. The “Trump of the Tropics” campaign became notorious for deeply racist, sexist, and homophobic rhetoric that, at its worst, encouraged sexual assault against women politicians, promoted violence toward LGBTQI+ communities, blamed homosexuality on “brainwashing and drugs,” and fostered nostalgia for Brazil’s former military dictatorship. Bolsonaro even claimed that the junta’s only mistake had been torturing dissidents when it “should have killed them instead.” These are among his many hateful statements, yet a substantial number of Brazilians embraced his tough-talking machismo, hoping he would restore order to the country. Bolsonaro went on to win the 2018 presidential election. His four years in office were marked by the rolling back of environmental protections in the Amazon, austerity measures, and a disastrous handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. After losing the 2022 presidential election, Bolsonaro disputed the results, and his supporters blockaded hundreds of roads for weeks in protest. This unrest culminated on January 8, 2023, when thousands of the defeated President’s most hardline supporters stormed and vandalized the Presidential Palace, Congress, and the Supreme Court in an alleged failed coup attempt that echoed the January 6 insurrection in Washington, D.C., two years earlier.

In his effort to market himself as a populist icon, Bolsonaro deliberately aligned himself with the Brazilian national team, frequently wearing the yellow canarinho jersey that came to symbolize his movement. He promoted the yellow-and-green kit as a rejuvenated expression of patriotism—one meant to distance the country from the corruption scandals that had produced a sense of national humiliation in the mid-2010s. Far-right protests in Brazil often became seas of yellow, as Bolsonaristas adopted the national team’s home kit as a kind of uniform in devotion to their leader. The canarinho shirts were especially prominent among those who ransacked the capital on January 8. As a result, many Brazilians on the left, as well as those simply disenchanted with the current political climate, have avoided wearing the yellow jersey, claiming it is “tainted.” Walter Casagrande, former World Cup player and member of Corinthians’ famously democratic 1980s squad, summed up the sentiment: “It’s the first time in my life I’m seeing the yellow jersey used against democracy and freedom. I now consider the Brazilian yellow jersey to have been kidnapped and appropriated by the right wing, so we cannot use it.”

In an effort to decouple right-wing politics from the Seleção, some left-leaning Brazilians have begun wearing alternative versions of the national colors. Some opt for the blue away jersey to show their support while avoiding associations with Bolsonaro. Some have suggested that Brazil adopt the white-and-blue color scheme that the national team wore prior to the adoption of the iconic yellow jersey in 1953. Others—particularly on the political left—have worked to reclaim the yellow jersey from the Bolsonaristas. During the 2022 FIFA World Cup, President-elect Lula announced that he would wear the famous yellow kit with the number 13 on the back, representing the Workers’ Party’s identification number, stating: “We can’t be ashamed of wearing our green and yellow shirts. They don’t belong to one particular candidate. They don’t belong to one particular party. Green and yellow are the colors of 213 million citizens who love this country.” Left-leaning pop stars such as Djonga, Ludmilla, and Anitta have worn the home jersey during performances in an effort to restore a more unifying national sentiment around the Seleção. Even Brazil’s largest beer brand, Brahma, released an ad campaign encouraging fans to wear the yellow jersey as a symbol of unity. Still, the famed yellow strip remains uncomfortable for some supporters, and further national healing will be necessary before it can fully shed its political associations.

Stoppage Time

Nevertheless, Brazilians have good reason to hold onto hope—not only for improved performances from the national team, but also for a future in which compatriots of all backgrounds feel united in their support. First, although Europe’s allure remains strong for Brazil’s rising stars, the domestic game is undergoing rapid growth. In recent years, Série A has seen a surge of investment through new foreign ownership groups, investor-friendly tax structures, and lucrative broadcasting deals. As a result, club revenues grew by 63% between 2019 and 2023. This financial strengthening has allowed teams such as Palmeiras and Flamengo to dominate continental competitions and pay competitive wages to elite players. In turn, high-profile European players—including Memphis Depay (Netherlands), Martin Braithwaite (Denmark), and Dimitri Payet (France)—have brought additional quality and visibility to what is increasingly regarded as the best league in the Americas. If this upward trajectory continues, young Brazilian talents may remain longer in the domestic system, increasing the likelihood that future national team squads feature more locally based players and fostering a stronger connection between the public and the Seleção.

Second, although the current squad struggled during qualification for this summer’s World Cup, it has shown glimpses of a team capable of playing a style of football that is both tactically coherent and aesthetically vibrant. In their emphatic 4–1 victory over South Korea at the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Brazil captivated global audiences with quick combinations; flowing sequences; and the flicks, feints, and stepovers that dismantled the Korean defense. After each goal, the players celebrated with choreographed samba routines set to the rhythm of caixa drums echoing from the stands. The joy was contagious, and their movement evoked memories of Brazil’s great sides of the past. Although their elimination at the hands of Croatia in the quarterfinals was disappointing, Brazil provided a proof of concept: a reminder that the flair of jogo bonito can coexist with the demands of the modern game. If this exceptionally gifted group can solidify a style that blends creativity with tactical structure, they may yet lift a sixth World Cup.

Finally, Jair Bolsonaro’s conviction—27 years in prison for conspiracy to plot a coup d’état—along with the arrests of several hardline members of his administration, marks a turning point in Brazil’s political landscape. In his inauguration speech, a choked-up and teary Lula proclaimed, “There aren’t two Brazils. We are one single people,” signaling an intention to heal the deep divisions of the previous era. Along with reversing several of Bolsonaro’s most harmful policies, Lula’s administration has placed renewed emphasis on reducing poverty and inequality, and on combating disinformation and hate speech. Although Lula’s own political past is far from unblemished, if his government succeeds in improving the lives of low-income Brazilians, genuine reconciliation and a more unified national identity may follow.

Brazil’s failures on and off the field at the 2014 FIFA World Cup symbolized a nation that had lost its identity, pride, and sense of purpose. A strong performance at the upcoming World Cup—one that reignites the national imagination—combined with governance reforms that tangibly improve citizens’ lives, could mark the country’s rediscovery of the rhythm and groove for which it is renowned.

Leave a comment